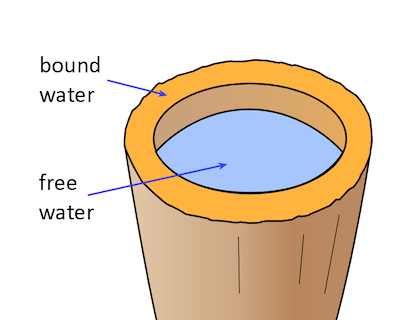

The drying process

showing the free water and bound water in the cell

When a log is freshly cut, the fibres contain a great deal of water, both in the cell cavities and the cell walls. Since the moisture in the cavities is free to evaporate once a cell has been cut, it is termed free water.

As the wood dries, the free moisture continues to evaporate until the cavity nearly dries out, after which the bound water contained in the cell walls begins to evaporate.

This point is called fibre saturation point, because the fibres are still saturated, even though the cell cavities are now almost dry. On average, this occurs in most species at around 30% MC.

Until fibre saturation point is reached, the biggest change in the timber is that it gets progressively lighter as the free moisture is lost. After fibre saturation point, however, the cell walls begin to shrink and get stiffer. This is the process of seasoning.

Equilibrium moisture content

Wood is hygroscopic by nature. In other words, it absorbs and releases moisture according to the environment. Eventually, all timber exposed to the atmosphere will reach equilibrium moisture content (EMC) – that is, a moisture content in balance with the surrounding air. So you can never ‘air dry’ a piece of wood to zero MC, because the air itself always contains some moisture.

EMC in most indoor coastal situations is between 10% and 15%. Once timber is seasoned, its MC will only change as the humidity, or moisture content of the air, changes. In very dry areas, such as inland, it may dry down to 6 or 7%.

Methods of drying

The two main methods used to season timber are air drying and kiln drying.

Air drying

Timber being air dried needs to be clear of the ground, with individual pieces separated by strips and spaced apart, so that the air can pass over all surfaces.

This enables the air to pick up the surface moisture and then drop down to the ground to discharge the droplets.

The biggest problem with air drying is that it can take a long time for the timber to reach EMC. Hardwoods typically take a year or more per 25 mm (one inch) of thickness to reach EMC. That is, a two inch thick board would take at least two years to dry to a seasoned state. So although it avoids the expense of using a kiln, it can be uneconomical in other ways, tying up stock and yard space for months or even years.

Kiln drying

Kilns have mechanical ventilation systems and heat and humidity controls to allow much faster drying under controlled conditions.

For slow-drying hardwoods, it’s often more economical to air dry them to fibre saturation point, and then kiln dry them to EMC. This means that getting the moisture down from 30% to 12% can be reduced to several days.

However, the higher temperatures in kilns do tend to create drying stresses, so it’s common at the end of drying to give the timber stack a high humidity treatment to relieve any internal stresses. Some hardwoods are also pre-steamed before the drying process begins to reduce the problem of collapse, where the cell walls buckle under the stress of drying.

For plantation softwoods, such as radiata pine, high temperature kilns are generally used. Unlike conventional kilns (which use temperatures of well below 100°C), radiata can be dried at up to 160°C, which allows small-section sizes to be dried in a matter of hours. The high temperatures also soften the wood constituents, particularly the lignin that bonds the fibres together, helping to overcome the problems of twist, spring and bow during the drying process.

Below is a chart showing a range of typical moisture content levels and the changes that tend to occur in the timber properties at these levels.

| Significant points in the drying process | ||

| Typical MC | State of timber | |

| Above 30 % | Green timber, where moisture loss occurs as free water leaves the cell cavities | |

| 30 % | Fibre saturation point, where evaporation begins to occur in the bound water contained in the cell walls. Shrinkage commences at this point | |

| 20 % | Resistance to most forms of fungal decay is achieved | |

| 10–15 % | Equilibrium moisture content, where the timber’s moisture content is in balance with the surrounding atmosphere. Timber is called seasoned | |

| 0 % | Oven dry timber | |

Definition of seasoned timber

Most formal documents, such as the Timber Marketing Act and Australian Standards, tend to say that seasoned timber must have a moisture content of 10-15 % ‘unless otherwise specified’. The reason for this proviso is that there are times when the end user of a particular product requires either a higher or lower moisture content.

Most formal documents, such as the Timber Marketing Act and Australian Standards, tend to say that seasoned timber must have a moisture content of 10-15 % ‘unless otherwise specified’. The reason for this proviso is that there are times when the end user of a particular product requires either a higher or lower moisture content.

For example, flooring products and high grade joinery items installed in climate-controlled buildings may need to be dried down to a lower level, typically 7-8 %. This is because air conditioning systems have the effect of de-humidifying the air, especially in buildings with sealed windows. In critical situations, timber products can be individually wrapped in plastic during the storage and delivery stages to ensure that they don’t absorb moisture from the air before reaching their final destination.

The Australian Standard that covers milled hardwood products (AS 2796), such as strip flooring, states that seasoned hardwood must have an MC range of 9-14 % unless otherwise specified.

Even then, it is still standard practice for flooring installers to ‘acclimatise’ timber flooring in the room it will be installed in for up to two weeks before the material is fixed in position. This enables it to each equilibrium with the local atmospheric conditions, which might be drier (e.g. in inland areas) or wetter (e.g. in tropical areas) than the normal MC range.

Some Australian Standards also make allowances for small variations outside the normal range for individual pieces in a pack of timber. The structural grading standards, for example, specify that at the time of grading, at least 90% of all pieces must be no more than 15%, and no piece may be more than 18% MC. These wetter pieces will progressively dry down to the same average MC as the other pieces in the pack anyway, and they’ll all vary slightly over time as the air humidity changes.