Strength-reducing defects

In the Visual characteristics lesson (from Section 2), we talked about some of the growth characteristics in timber that are used to grade or sort boards according to their appearance. These features include: grain, figure, texture and colour.

Appearance grading standards are used to assess boards where the surface finish and visual features are important – such as in flooring, lining boards, skirting, architraves, furniture components, and so on.

By contrast, structural grading standards are used to assess boards in terms of their strength. Structural grading is also called stress grading, since the main criterion of assessment is how much stress the board will be able to withstand before it fails under a load.

Growth characteristics that have a strength-reducing effect – such as knots and irregular grain – are now considered to be defects rather than features, and any visual appeal they may have is no longer a consideration.

Having said that, it is also possible to give timber a structural appearance grade, which takes into account both the strength and appearance qualities of certain characteristics. These grades are covered in ‘Grading card’ downloads linked in the next lesson: Visual stress grading techniques.

Let’s now look more closely at the main types of strength-reducing defects found in structurally-graded timber. For details on the actual limitations that apply to these characteristics in the visual stress grading standards, follow the links in the next lesson to the various downloadable documents.

Knots

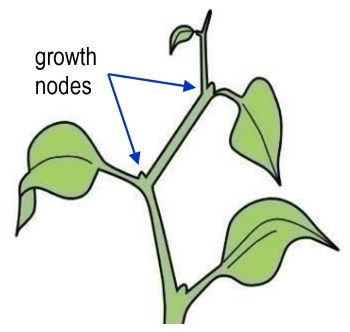

Knots are branches from the growing tree that have been cut through when the log is re-sawn. All branches start their life as tiny growth nodes. As a branch grows bigger, its diameter increases proportionately to give it extra strength.

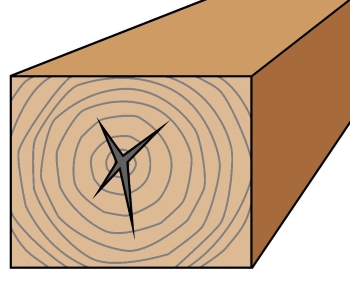

This is why knots tend to be smaller on the side of the board that’s closest to the middle of the tree. In the very centre, at the pith, the branch will have tapered back to virtually nothing.

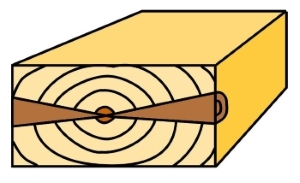

The block of wood at right actually has two separate branches emanating from the pith. In a full length board it would be easy to mistake these two knots for a single branch (that is, two sides of the same knot) – until you notice that the pith is running through the centre of the board.

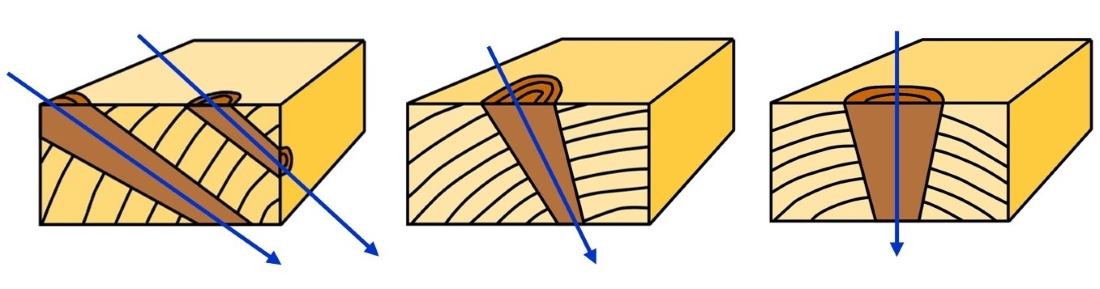

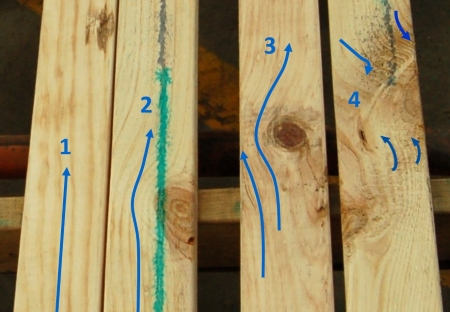

Knots tend to look different on boards that are more backsawn or more quartersawn, because they have been cut through at different angles. Below are some examples.

(Note that the arrows point to the pith)

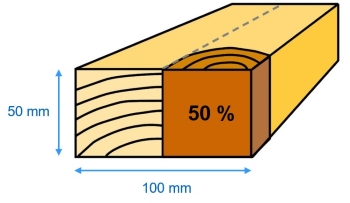

Knots reduce the strength of a board because they take up space that would otherwise be occupied by the wood fibres running lengthwise.

For example, if a 100 x 50 board had a knot like the one shown in the diagram at right, it would reduce the effective cross sectional size of the board at that point to 50 x 50. This is because the other half of the board has a branch that runs across-ways, which contributes nothing to the bending strength along the length of the board.

The position of a knot on the face (or edge) of a board – such as whether it is in the centre of the face or closer to the edge – has a significant effect on the amount of strength it takes away from the board. For more information about knot measurement and assessment, see the downloadable attachments in the lesson: Visual stress grading techniques.

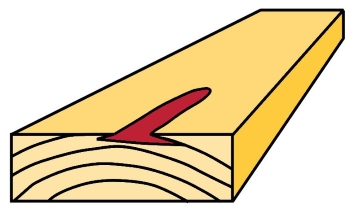

Resin pockets (softwoods)

When a softwood tree suffers an injury, it tries to patch up the damaged area with resin, in order to stop insects and fungal spores from entering through the wound.

In the re-sawn board, this damaged area will show up as a resin pocket, which may still be weepy when the timber is green. Once the board has been seasoned, the resin often crystalises and falls out, leaving a void behind.

Resin pockets, bark pockets and overgrowths of injury are put into the same category in softwood structural grading, because they are often associated with each other and all have the same effect on the strength of a piece.

Technically speaking, the differences between them are as follows:

Resin pockets are cavities which contain (or have contained) resin.

Bark pockets are patches of bark that have been encased in wood tissue.

Overgrowths of injury are areas of dead or damaged wood that have been overgrown by new wood, often combined with resin.

Gum pockets and veins (hardwood)

Hardwood trees have similar defence mechanisms to softwood trees when they’re damaged by fire, insects or mechanical abrasion.

However, the chemical composition of the gum, kino or latex used to patch up the damaged area is different from the resin commonly found in softwoods, so when these pockets occur in hardwood timber they’re generally called gum pockets.

The hardwood structural grading standards impose limitations on the following types of related defects:

(on the end, where there are bridging fibres)

that becomes a loose gum vein

(on the edge, where there is

a complete separation of fibres).

Gum pocket – cavity which contains (or has contained) gum

Loose gum vein – separation of fibres caused by a continuous layer of gum

Tight gum vein – separation of fibres caused by gum, but bridged by wood tissue at close intervals

Included bark – strands of bark that are trapped between the wood fibres, having the same effect as a loose gum vein

Overgrowth of injury – area of dead or damaged wood that has been overgrown by new wood, often combined with gum.

Checks, splits and shakes

There are various forces that can cause wood fibres to separate and show up as cracks in a board. Sometimes they occur in the growing tree, other times they develop while the timber is drying, and they can also happen due to mishandling.

The most common types of cracks or fissures in the grain are checks, splits and shakes. Because they have different effects on the strength of timber, they are treated differently in the structural grading rules.

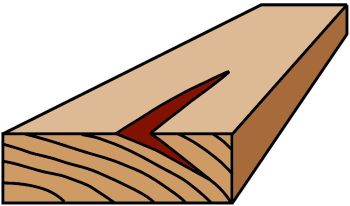

Checks generally form as the result of drying stresses, where the wood fibres pull away from each other because different areas are shrinking at different rates.

They always run lengthwise with the grain, and their depth is radial to the growth rings – that is, towards the centre of the tree.

It’s important to remember that a check does not go from one surface to another. When this happens, it is called a split.

Splits occur when there is a lengthwise separation of fibres that runs from one surface to another surface. It sometimes occurs when a drying check gets so bad that it goes right through the piece, particularly on the end of a board.

Splits in the body of the piece are not permitted at all in structural grades. On the ends they are called end splits, and are only permitted within strict limitations.

Shakes occur as a result of internal stresses in the standing tree or in the log during felling or conversion to sawn timber.

There are several types of shakes, such as heart shakes, ring shakes and cross shakes. The diagram at right shows a heart shake, which radiates from the heart of the tree, often in the form of a star pattern.

For more details on the different types of shakes and their grading limitations, see the downloadable attachments in the lesson: Visual stress grading techniques.

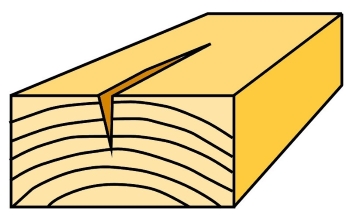

Sloping grain

Timber is strongest when the grain is straight and runs parallel to the length of the board. The more it deviates from straight and parallel, the weaker it becomes.

When there is a general slope in a board’s grain, it needs to be considered as a strength-reducing defect and graded accordingly.

| Sloping grain: | |

| Board 1: | straight grain – very strong |

| Board 2: | local deviation of grain around a knot – less strong, but allowed for when the knot is graded |

| Board 3: | minor sloping grain – but mostly a local deviation, so not serious |

| Board 4: | potentially serious grain deviation in the boards above – not just across the width, but also coming up towards the face from inside – characterised by surface chip-out and a fuzzy finish |

Note that in softwoods, it’s common for the grain to deviate around knots. As long as this is limited to a local deviation, it doesn’t need to be separately assessed, because the grade limitations on the knot sizes make allowance for it.

The same thing applies to variations in the grain as it curves along a piece – if the deviation is no more than half the width of the piece, it can be considered ‘localised’.

Sloping grain can sometimes be tricky to detect by eye, because the growth rings often run down the length of the board and make you think that the grain is doing the same thing.

But remember, growth rings are the alternation of early wood and late wood, and they form different patterns on the face of a board depending on the way it’s been cut from the log. The grain, on the other hand, is the direction of the wood fibres, and it may or may not run in line with the growth rings.

If you’re in doubt about what the grain is doing in a particular area of the board, you can find out by:

looking for surface checks – these always follow the grain, because they’re caused by the fibres pulling away from each other as the timber dries

splitting a small portion of wood off the board to separate the fibres, because the split or slither of wood will also follow the grain.

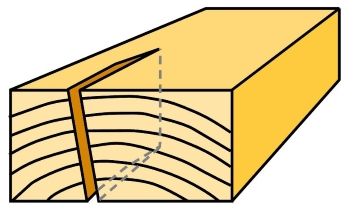

Want or wane

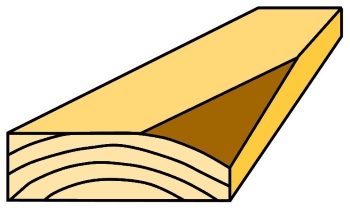

Want and wane are caused by different things, but because they have the same effect on a piece of timber they’re both measured and assessed in the same way.

Wane is the appearance of the underbark surface of the log, which causes some of the arris to be missing on the piece. Sometimes the surface is smooth, but other times there is still bark attached.

Want is the absence of wood from the surface or arris when it’s caused by anything other than wane. For example, forklift damage or abrasions from chains can break off the edge of a piece and result in want.

Minor instances of want or wane don’t generally have a significant effect on strength, although they can still affect the utility (or ‘useability’) of a structural timber component. This particularly applies to roof truss components secured with nail plates, since the holding power of the teeth depends on them being able to embed fully into the timber.

Other defects

There are various other defects that need to be considered when visually stress grading timber for structural purposes. Depending on whether you’re grading softwood or hardwood, these include borer holes, termite galleries, fungal decay, lyctid susceptible sapwood, brittle heart, compression failures and fractures.

The attachments in Visual stress grading techniques have more details on how to measure and assess the strength-reducing defects listed in the following two Australian Standards:

AS 2082 Timber - Hardwood - Visually stress-graded for structural purposes

AS 2858 Timber - Softwood - Visually graded for structural purposes

You don’t need to know all of the limitations that apply to these defects unless you’re involved in visual stress grading in a sawmill or other manufacturing operation. For general quality control purposes, you only need to be aware of the types of defects that can appear in a board and the reasons for their occurrence – such as whether they’re growth characteristics, drying faults, handling damage, and so on.