Visual characteristics

Experienced timber workers are generally able to identify the different species they regularly work with just by looking at the surface of the timber. This is because most species have distinctive sets of characteristics that give them a typical appearance.

Many of these visual characteristics also form part of the selection criteria or grading requirements for particular end uses – especially when the timber is used in flooring, lining boards, furniture, musical instruments and decorative products.

Below are descriptions of the variations that occur between different species in terms of grain, figure, texture, colour and reaction wood. We won’t cover visual characteristics of knots, gum veins, resin pockets and other features that have a strength-reducing effect on a board, since these are discussed in detail in other sections covering ‘softwood structural grading’ and ‘hardwood structural grading’.

Grain

the general direction of the grain

follows the natural contours of the log

Grain refers to the direction of growth of the wood fibres. In general, the fibres tend to run parallel to the length of a piece of timber, since that’s the way the timber will have been sawn from the log.

However, there are various reasons why the grain may deviate from a straight parallel line, and it is unusual for an individual piece to be ‘straight-grained’ throughout its entire length.

Some of the reasons result from the sawmilling process, such as when the log has a natural curve (called a ‘sweep’) and the direction of the cut is not in line with the grain alignment.

The photo at right shows a board that has been cut from a log with a sweep. When this board is resawn and the natural edges are removed, the finished board will contain sloping grain that runs towards the right hand edge.

Other reasons relate to the growth characteristics of the tree, and include spiral growth, reaction wood and grain deviations around branches and internal defects.

The easiest way to tell which direction the grain is running in is to look for surface checks (small cracks) in the timber. Surface checks occur when the wood fibres pull apart from each other as they shrink, so the checks always run with the grain. Another method is to pull up a small splinter with a knife and see where it runs. A more destructive method would be to split the piece and look at the direction of the fracture.

The terms used to describe different types of grain include:

-

straight – grain that runs consistently in a single direction, common in western red cedar and Tasmanian oak

-

spiral – grain that results from wood tissue growing in a spiral around the centre of the tree, quite common in radiata pine

-

interlocked – grain that results from a double spiral, where alternate bands of growth run in opposite directions, often found in brushbox, grey gum and other hardwoods that are difficult to split

-

wavy – grain that produces a wavy pattern on the surface of the timber, common in spotted gum and jarrah

-

irregular – grain that swirls or twists, particularly around burls, knots and other growth features, sometimes called ‘cranky’ grain by woodworkers.

Figure

Figure refers to the patterns formed on the surface of timber by the grain, growth rings, colour variations and other characteristics in the wood. In general, the patterns are related to the way the timber is cut from the log.

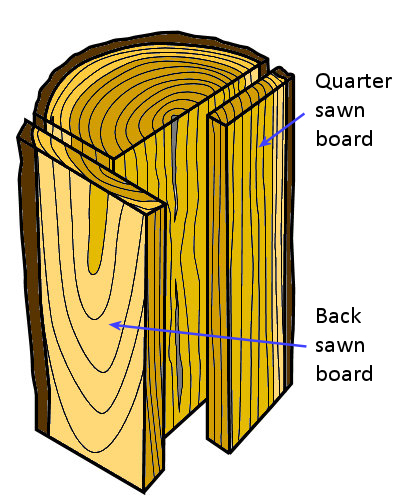

The diagram at right shows the difference between the two main types of cuts used by sawmills to break down a log.

-

Backsawn timber is cut at a tangent to the growth rings (so that the rings are less than 45o to the end of the board). This cutting pattern can produce various types of figure, including cathedral, with looping growth rings, particularly when they form a V shape.

-

Quartersawn timber is cut radially towards the centre of the tree (so that the growth rings are more than 45o to the end of the board). This can produce figures such as fiddleback (typical used on the backs of violins), tiger stripe and ribbon, which are all related.

There are many other terms used to describe particular types of figure, often with names that suggest various images, like cat’s paw, bird’s eye and bee’s wing.

Texture

Texture is determined by the size and density of the fibres and their distribution in the wood tissue. It is often described in the following terms:

the result of prominent growth rings

in a western red cedar board

-

fine – such as in brush box, river red gum and radiata pine

-

moderately coarse – such as in alpine ash, blackbutt and spotted gum

-

coarse – such as in meranti, American white oak and Douglas fir (oregon).

In addition to the above terms, the texture can also be described as:

-

even – characteristic of most hardwoods and some softwoods

-

uneven – found in timbers that have prominent growth rings, such as western red cedar, radiata pine and Douglas fir.

Colour

There are various factors that influence the colour of timber, and the variations that may occur in a single piece. The main determining factors are the chemical make-up of the extractives deposited in the heartwood and the composition of the woody fibres.

Durable species often look darker and richer in colour than non-durable species due to the heavy deposits of toxic extractives in the heartwood – although there are some notable exceptions to this general statement, so it shouldn’t be treated as universal rule (see: Durability).

Timber species can range from almost white, such as in balsa, through to virtually black, such as in ebony. In between are many shades of different colours, including yellows (e.g. huon pine), pinks (e.g. Victorian ash), reds (e.g. the eucalypts that range from light reds through to dark reds) and browns (e.g. blackwood).

Some species also have a distinctive colour difference between the sapwood and heartwood. Again, this is mostly due to the extractives found in the heartwood. In timbers that are typically cut from smaller logs, like cypress pine, the interplay between the sapwood and heartwood is a characteristic feature of the species that forms part of its visual appeal – as shown in the photo at right.

Reaction wood

Although reaction wood is really a structural defect in grading terms, it’s included in this lesson because of the effect it has on the grain and figure in a piece of timber.

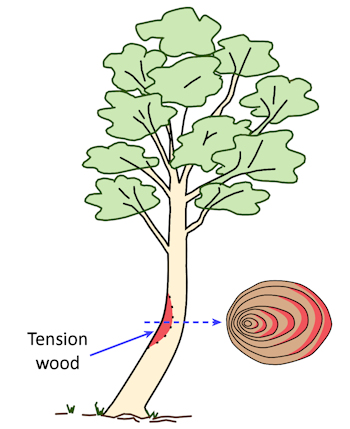

Trees that grow naturally on a lean will generally develop coping mechanisms to compensate for the lopsided centre of gravity. This includes reaction wood in the stem. Reaction wood is formed to counteract the additional stresses placed on the stem. It is also a normal characteristic in branches, because of the angles they grow at.

|  |

| Tension wood in a hardwood tree | Compression wood in a softwood tree |

In hardwoods, reaction wood forms on the upper side of a lean, or on top of a branch, as tries to pull the trunk or branch in an upward position. The wood formed is therefore under tension, and so is termed tension wood.

Tension wood has a higher cellulose content, so the cell walls tend to be thicker than in normal xylem tissue.

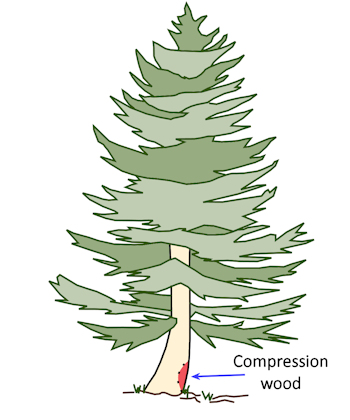

In softwoods, reaction wood occurs on the underside of a lean or the underside of a branch. Because the wood tissue is under pressure from above, it is called compression wood.

Compression wood tends to be darker than the surrounding xylem tissue and reddish in colour, due to a higher lignin content between the fibres.

Reaction wood is weaker than normal woody tissue, because the fibres are not running in an even longitudinal direction. The swirly grain also tends to produce a fuzzy finish when the timber is cut or sanded, since the fibres are sticking up at odd angles relative to the surface of the board.